ourstory's history

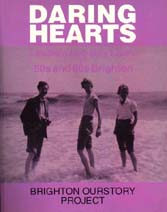

Daring hearts

Book published 1992

The following are extracts from 'Daring Hearts: Lesbian and Gay lives of 50s and 60s Brighton' published by Brighton Ourstory Project in 1992 by QueenSpark Books (ISBN: 0904733319).

This edition of Daring Hearts is out of print.

This edition of Daring Hearts is out of print.

If you wish to quote from this page or Daring Hearts itself, please contact us first for permission.

You might also be interested in our other publication, which is still in print: Just Take Your Frock Off: A Lesbian Life.

Sandie:

We came down on holiday, a week's holiday, and it was the freedom in Brighton. There were so many gay people and they seemed to be accepted and there were clubs for gay people... ohh, wonderful! It was absolutely Mecca because it was very gay then. Brighton's gay now but it was very, very gay then.

Siobhan:

Brighton represented for me an escapism from my own anger, from the struggle of my own life. I had a different feel about myself when I was down here... I preferred myself... there wasn't that sense of stress that there seemed to be with London at all.

Patrick:

When I was at school the Spotted Dog was the only place that was known as a queer bar; wasn't known as a gay bar 'cause we didn't use the word gay then. But it was a dare at school for 2/6d if you dared to go through the door, not to buy a drink, but if you actually dared to go through the door. But if anyone wanted to take the piss out of you at school they'd say, 'Oh you know Patrick Newley's been to the Spotted Dog.' None of us ever, I don't think, ever had the nerve. It was even a sort of nerve to go into the same street as the Spotted Dog. But that was the only place that we knew that was gay. It was sort of frightening.

Jo:

He says, 'But I can't believe that pretty girl over there, she looks like my daughter, how can she be a lesbian?' and I say, 'Well that's it Harry, it takes all sorts to make a world, how do you know your daughter's not a lesbian?'.

Vicky:

The dice was really loaded against you, in many respects. I mean, you couldn't get a loan from a bank without a man to guarantee you. You couldn't buy anything on HP without having a man to guarantee you. I mean, a woman was definitely a second class citizen, without a doubt. They talk about inequality nowadays but you've got no real conception of what inequality was unless you lived then.

Aileen:

Harriet went to work on the buses. I lived in Church Road, Hove, and there was a bus stop just facing the kitchen window and she'd phone me up and she'd say, 'I'm passing at such and such a time, watch out for me.' And she'd pass by and suddenly the back door of the bus would fly open. She'd be there waving away. Couldn't believe it! And, of course, everybody on the bus would be looking. Ah dear, it was so funny. And I'd be hiding behind the curtains.

Buck:

I came down to Brighton. I went to work at Clarges hotel, as a trainee receptionist, where I stayed seventeen years and finished up marrying the governor which causes much laughter amongst most of my friends. In fact I was married three times. Every time I got lonely, I got married. I'm not sure whether it's the bouquet or the white dress, but none of them lasted very long. I think it was out of sheer loneliness. Loneliness is the worst ship that ever set to sea.

George:

This is a true story to show you what I mean about fear. When Steve moved into Sackville Gardens in Hove I decided to go and sleep the Saturday night there with him. Now I went in there very late at night so nobody would see me come in but during the night unfortunately it snowed really heavily, really heavily, so then when you got to the front door it was pristine, okay, and there was no way I could go out of that door in case someone saw me and those footsteps would show he'd had someone in his room for the night. So I stayed there till three in the afternoon until they cleared it and they'd all gone and I snuck out.

Peter:

It was part of the excitement, was the secrecy. It was all hush-hush and there was a certain amount of suave in it, in those days, which there isn't now, it's lost. The queens these days, they go camping it around quite openly, and it's lost something. It's lost a bit of its charm about it, the fact that it's no longer a secret... It's lost a certain of its colour for the fact that it's no longer slightly underground.

James:

You had to be careful about taking and keeping photographs. The whole thing was so illegal. The police could take your family album, your photograph album and ask, 'Who is this? Who is that? What is going on here?' It was too risky.

Vicky:

I think there were a few lesbian couples that I knew where one had children from a previous marriage that was brought up as a family. But they always lived in bloody awful fear of anybody, of the father finding out that the woman was a lesbian, because I think it was always thought that the children would be taken away.

Sandie:

I was always in a permanent relationship. It's just that there were quite a few of them! But every time I went into a relationship, it was always with the idea in mind that it was going to last forever. I had a Mills and Boon idea of love.

Grant:

Brighton queens all wore terribly flared trousers and terribly Hawaiian shirts with all sorts of tulle at the neck. Hairdos were rather flamboyant, it was all out of a bottle. Handkerchiefs, kerchiefs round their necks for scarves. Jewellery, of course, was the greatest thing, they loved jewellery; they used to have not one bracelet but about four. And rings on everything except the thumb. Colour-wise it was a bit grotesque. Pink velvet trousers with a green shirt. Rather like Quentin Crisp. Everybody smoked and invariably you could find a queer by the way he held his cigarette.

Barbara:

You would always have a little finger ring on your left hand, that was another sign. So if somebody was out in the gear, you'd give them the glad eye or they'd give you the glad eye. You always had a little finger ring, whether you were butch or fem. Or you'd wear a wedding ring if you were fixed up with somebody, on your other hand. There you are, third finger right hand, still wearing mine, wouldn't come off now, beautiful wedding ring, worn so thin.

Patrick:

Brighton has always had a gay mafia - all those expensive queens, you know, throwing cocktail parties, with art dealers and old actresses. It was a very closeted place, there was an awful lot that went on behind heavily brocaded curtains. Robin Maugham lived down here and had crowds of the camp coming to visit. Terence Rattigan had a house here. Collie Knox, Dougie Byng, Gilbert Harding, Alan Melville, Sir David Webster... And Godfrey Winn lived out at Falmer. And they'd all have these pink champagne and sherry dos - 'Oh, we must invite Enid Bagnold'.

Harriet:

Some of the butch women made awful remarks: 'The wife's at home cooking lunch' or something and it was absolutely appalling. It must have been like being married to a man, if you're going to put up with that nonsense. One of them, tiny little thing always used to wear bow ties and trousers and collars and shirts and everything. She even used to wear little Y-fronts.

Kay:

Sex and money was at the heart of the gay community in Arundel Terrace, Lewes Terrace and Chichester Terrace. It was an upper-class jungle. When I came here it wasn't such a mixed social group as it is now. The terrace had a class thing about it, moneyed thing.

I would be invited to cocktail parties, which isn't my thing. Gay males, rich, living in swanky, elegant - piss elegant - places, ghastly taste, actually, to my mind, with the interior decorator boyfriend. They considered themselves classy; worked in the Theatre, banking, stockbrokers. They had all these cocktail parties full, also, of what we called the bridge ladies who liked faggots. And theatrical lezzies. Nothing was worse than theatrical lezzies of that period. They were even more superficial than anyone. They quarrelled all the time, they drank too much. They were all refined and ladylike, as it were, and then suddenly you'd realise they'd just had too many gins, so they'd start on each other: snip, snip, snip, snip. Sad. I don't think they liked me, really, because I wouldn't play.

Michael:

Coming from a town like Luton to Brighton was like arriving in Disneyland. All the wonderful Regency buildings and the seafront. And a big gay culture, clubs and so on, which was very unusual for a provincial town of its size.

Jo:

Now I'm trying to think when I started coming to Brighton. I suppose it was in the fifties, the early fifties. What were the clubs? There was one called Pigott's, on the corner of Madeira place and St James's street, and there was a hotel next door, called the Atlantic. There weren't any gay hotels then, you know, so I'd stay at this Atlantic, which was straight, but we knew it and it was quite clean and wholesome and central. My mum and pop used to come and stay in it as well, and I used to bring whichever bird I happened to be with for a dirty weekend. And then there was the Greyhound, we used to go there, the 42, which although it was mainly boys, if you were an accepted woman and not a sort of diesel dyke looking for punch-ups, they let you in. But the Curtain was very, very nice, that was very mixed.

Vicky:

We had a wonderful holiday. We stayed in a bed and breakfast place in Hove, which was very smart. I don't think they knew what had hit them when we arrived. Oh God! It was absolutely dead straight and we arrived there, dear, all hell let loose and there were silences when we went into breakfast. Still, we had a really good holiday.

Grant:

But then, things were different then, they used to come for a fortnight's holiday. I can remember lots and lots of friends phoning me up or writing and saying 'Ooh, we're coming to Brighton for our usual holiday, we're staying at so-and-so, can we meet you?' Well, they don't come to Brighton now for their holiday. They just don't come. And that stopped at the end of the sixties, beginning of the seventies. They started going abroad. Holland, Morocco, Spain.

James:

One of the classiest bars was the Argyle Hotel in Middle Street. That was a very, very select hotel, very expensive, but very small. Presided over by two ladies, two sisters, the Misses Brown or, as everyone used to say, the Miss Browns, in those days. We're quite sure they didn't really know what was going on but it was a very smart cocktail bar...

Two barmen were there, very, very smart in their dark red jackets, Tony and Michael, and they were always called the Duke and Duchess of Argyle...

Those were marvellous days. There was always a real pianist, an Oriental boy who'd played in swish hotel bars in Singapore, and he was there for some years playing songs from shows, which suited the clientele very well indeed. And I can always remember a very shy young man with thick, black hair brushed back, who used to stand at the far end of the bar, a customer, who wouldn't talk to anybody, and I can remember Tony and Michael saying, 'One day that man is going to be a star because he is the most fabulous drag performer and a total extrovert once he gets into a frock, but terribly shy out of it.' And that was Danny La Rue, who would stay there.

Sandie:

Oh, the Lorelei coffee bar, yes, we used to half live in there, yes, loved it. In the very beginning, they used to open on a Saturday night, after the clubs had closed... we all would go round camping through the streets at all hours of night and early morning, you know, singing loud songs, one thing and another. We used to behave outrageously, really, when you think about it. But, yeah, we used to land up in the Lorelei and it would be crammed to the doors, you know, just drinking coffee.

Dennis:

I remember coming down from Bradford and apart from The Spotted Dog and Terry's Bar, the Greyhound was gay, presided over by a succession of old queens but that was a bit of an elephant's graveyard really. And the 42 Club was the only gay club in the fifties. On the seafront. In its heyday, in the fifties, the 42 Club was packed 'cause it was the only gay club really. And then Ray opened another one up Middle Street called the Variety Club, which is where the school is now. And so there were two gay clubs. And then a whole profusion of gay clubs just sprang up, all small ones. There was the Regency Club in Regency Square, there was the Queen of Clubs, which Ray opened in Bedford Square, and then, of course, there was the Curtain Club.

A guy called Eddie Duff opened that: big, fat, South African man with an Italian boyfriend called Tina. It was all rather nice but rather sedate. It was open in the afternoons and there was a grand piano tinkling away. I mean, it was just really a bar and there was a bit round the back that had a dancefloor but I never saw anybody round there at all, ever People just congregated round the bar and simply drank and listened to the pianist and it was all rather nice, rather genteel. Everybody there was homosexual but you wouldn't call it gay.

It was just a mutual meeting place and most of them, the 42 Club, the upstairs bar at the Greyhound, the Spotted Dog, you got all age groups there; they weren't old but at the same time, everybody sort of behaved themselves and kept a low profile and it wasn't outrageous.

It started to liven up towards the end of the sixties, when everything else started to loosen up, when things had got gay and we had got flower power.

Well, of course, they had it down here with a vengeance as you can imagine they would. And Ray Bishop took the Heart And Hand in Ship Street and that became very gay indeed, a sort of Aquarium of its day. And then he took the Curtain Club and made that very gay and there was a disco put in with disco lights... and the whole place started to swing.

All text on this page © Brighton Ourstory